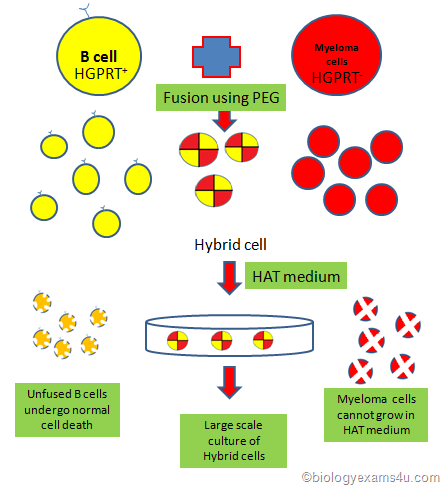

Immunogenicity is the ability of a molecule to solicit an immune response. Without T help, the humoral response shuts down in fact, the cellular response shuts down as well, as in AIDS. The T cell receptor of a T helper lymphocyte then binds the MHC II/antigen and the T cell secretes cytokines that signal the B-lymphocyte to divide, differentiate and secrete antibodies. This MHC II/antigen complex is then expressed on the plasma membrane of the B-lymphocyte. The endolysosome fuses with a vesicle containing class II Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC II) molecules and the peptide antigens are bound by a cleft in the MHC II. This endosome then fuses with a lysosome and the resulting endolysosome digests the antigen into small peptides. Crosslinking of many mIgM and antigen molecules occurs (capping) and the complex is then taken into the cell by receptor mediated endocytosis.

B-lymphocytes use membrane IgM (mIgM) to bind antigen in its native form. The humoral response targets extracellular antigens. This is a general description of the cellular immune response, which targets intracellular pathogens such as viruses or bacteria (non-self) and cancer cells (altered-self), based on the presentation of these antigens on their plasma membrane. If the T cell receptor of a CTL binds to the MHC I/peptide antigen on a cell, the whole cell is destroyed. The MHC I presents endogenously derived peptide antigens to cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL).

Humoral immunity involves soluble proteins found in serum (antibodies) that can be transferred to a recipient when serum is transfused.Įvery cell in a vertebrate organism expresses the class I Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC I) on its plasma membrane. The cellular immune response is mediated by T lymphocytes and cannot be transferred from one individual to another by transfusion of serum. Immune protection is provided by a dual system consisting of the cellular immune response and the humoral immune response. The surveillance is mediated by proteins and cells that circulate throughout the organism to identify and destroy foreign cells, viruses, or macromolecules. The immune system is a surveillance system designed to provide protection to its host from foreign invaders. Procedures for generating, purifying, and modifying antibodies for use as antigen-specific probes were developed during the 1970s and 1980s and have remained relatively unchanged since Harlow and Lane published their classic book "Antibodies: A Laboratory Manual" in 1988. Adjuvants can be mixed and injected with an immunogen to increase the intensity of the immune response.Ĭarrier protein conjugation, use of adjuvants and other issues relating to preparation of samples for injection are described in this section on antibody production. For antibody production to be successful with small antigens, they must be chemically conjugated with immunogenic carrier proteins such as keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH). Even so, equipped with a basic understanding of how the immune system responds to injection of a foreign substance and a knowledge of available tools for preparing a sample for injection, researchers can greatly increase the probability of obtaining a useful antibody product.įor example, small compounds (drugs or peptides) are not sufficiently complex by themselves to induce an immune response or be processed in a manner that elicits the production of specific antibodies. Individual animals-even those that are genetically identical-will respond uniquely to the same immunization scheme, generating different suites of specific antibodies against an injected antigen.

However, because it depends upon such a complex biological system (immunity of a living organism), results are not entirely predictable. Antibody production is conceptually simple.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)